- Home

- David Adams

Faith

Faith Read online

Faith

David Adams

Copyright David Adams 2012

Faith

“Faith isn’t faith until it’s all you’re holding on to.”

- Toralii proverb

Kael’jax Internment Camp, Kaater Mountains

Toralii Homeworld of Evarel

Three hundred and four years ago

“I know my mother’s dead.”

Simple words spoken by a simple child. Tami looked up to the priest, the rags the Neralanese charitably labelled clothing dangled limply off her, white fur thinning and falling out. The flesh of her toes, visible through what was left of her pelt, were blue and black from too many winter nights with too few blankets and no shoes.

The Toralii priest, his features falling at the proclamation, placed his emaciated paw between the girl’s fuzzy ears gave her a comforting pat.

“You’re only nine,” Guardian Antani Silari chided. “You don’t have an understanding of these things. Cubs don’t know what happens when people go to the Gods. As a matter of fact, most adults don’t either. It’s something that takes a lifetime of wisdom to understand and a complete picture is only obtained when you, yourself, pass.”

The girl tilted her head. She, unlike most children, didn’t mind when people touched between her ears. It was comforting, an echo of her past, something to remind her of her family and life before the camp.

There wasn’t much to remember. A few flashes of memories, a handful of words and phrases spoken by people she barely remembered. Words of courage as the energy mortars fell around them, words of comfort for loved ones as countless Autiellan women and men went out to fight the Neralanese and never returned, words of strength when the dark times seemed entirely endless.

“I know what happens when you go to the Gods,” Tami replied, sincere but flat as though she were reciting some fact in her school’s textbook. “The Neralanese take you and throw you in the incinerator they have in the middle of the camp.” Another pause. “Is the incinerator some kind of portal to the Gods?”

Antani’s hand fell away from the child’s head, his voice quietening. “Who told you that?”

Tami blinked a few times, her face scrunching up as she tried to understand why what she said was wrong. “Nobody told me,” she answered, “I saw Zumarl and Izkadi throw Mother’s body in there this afternoon. So I know what happens when you go. It’s nothing like the stories you tell.”

Antani shook his head. He took two paws, cupping them together to form a ball. “The journey to the Gods is... only a metaphor, child. The body is but a shell,” he said, moving his paws apart as though revealing something within. “Just a container for the soul. When a Toralii dies, if they have been honest and true throughout their lives, their soul departs the body and flies up towards the Sky Gods. There, it’s reunited with the mighty forces who created it, to live forever amongst the stars.”

“Oh.”

It was a simple answer, but simply and precisely articulated Tami’s feelings on the matter.

Antani turned his gaze upwards and pointed with a thin finger, his paw making a sweeping gesture across the twilight sky dotted with pinpricks of light struggling to be seen through the harsh floodlights of the camp. “Look to the heavens, child. See all the stars?”

Tami nodded. From somewhere else in the camp there was a shout, then a shriek, followed by the high pitched crack of a Toralii slugthrower. Then silence. Searchlights illuminated the far corner of the camp—another escape attempt. The Neralanese guards, their forms highlighted in the spotlight’s glare, picked up the woman’s body and began dragging it towards the central incinerator. Tami and the priest carried on as though nothing had happened.

When Antani spoke, his voice was soft. “Those stars are the balconies of the Sky God’s palace. From there our ancestors, and our friends who knew us in life, can look down on Evarel and see all that we do. That’s how they know if we’ve been righteous in our lives so when we pass, we too may go to the Gods and join them.”

Tami canted her head, looking upwards. “So my mother’s up there watching me? Watching me right now?”

Antani smiled, nodding his gray-furred head. “I suspect that she is,” he said. “At least, if the balconies are not too crowded this evening.”

The girl stared up at the sky, focusing on the brightest star she could find. She imagined it as a faint, shimmering balcony, so far away she could not make out the details. “Do you think they have a lot of food up there? Fresh water? Big, thick, fuzzy blankets?”

Both had become accustomed to the hunger, the thirst, the cold, but had memories of better times. Imagining the biggest, warmest blanket she could, the girl drew comfort from the thought—it didn’t stop her little body from trembling, though, but she had become used to it. Every night was cold, some more than most, but her thoughts on the matter were quite simple. They either survived or they died. Talking helped keep her warm.

“I’d imagine that they have everything their hearts desire,” Antani replied, his tail wrapping around himself for additional heat. “Food, water, warmth and shelter...”

There was another pause.

“Are there Neralanese in the Sky God’s Palace?”

The Toralii priest did not immediately answer, carefully phrasing his words, speaking slowly and deliberately. “The Palace allows access only to those who are good of heart,” he explained, “So... it’s not impossible for there to be a goodly Neralanese or two up there. But I’d imagine there aren’t many. And I’d imagine that there are fewer still drawn from those who... ‘share’... our lands.”

“Are there camp guards up there?”

This the priest sounded certain of. “No, child.”

Tami nodded her head, seeming pleased. “That’s good. I hope none of the other Neralanese up there turn into guards. I want my mother to get her food from the crops, or from a store, or a market... not from guards she has sex with.”

Antani stared in bewilderment at the young child, his tail twitching in surprise. “T-Tami, where did you hear that? Did your mother tell you what she was doing...?”

Tami smiled, a sad, proud smile that belied a complex mix of emotions, and shook her head. “Oh, no, I figured it out on my own. I’m not stupid. Children don’t get separate rations, they’re supposed to share their parents’, but I’m nine now. I eat a lot.” Her voice softened as she recounted her memories. “I tried to eat as little as I could, but I get really hungry... and I know Mum had to be finding food somehow, since we somehow got extra whenever we needed it and there’s not many ways you can get it around here. Mister Belaran told me that’s how he got the extra rations for his sister, so I figured Mum was doing the same thing.” She sighed, shaking her head. “I knew what she was doing right away. She would often come back to our cell late, with bruises in places where people usually don’t get bruises, and when she thought I wasn’t looking she’d cry a lot. It’s a good thing Dad’s dead, or he might be sad.”

The little child smiled again, expecting the Toralii Guardian to be proud of her cleverness. “So, yeah. I figured it out on my own.” She shuffled closer to the male, trying to draw some warmth from the thin pelt covering his body. “I think Mum did it so they would leave me alone...”

Antani drew the girl to him, holding her gently since he knew his fingers were bony and gaunt. The child was nine, yet knew so much about the dark place in which they had found themselves... far too much for a child of her age. “I can say this, Tami... nobody has any harm come to them in the Palace.”

“It sounds nice,” said Tami, wistfully staring up at the sky.

Antani nodded his sincere agreement. “It is. It’s a paradise. Your mother has everything she ever wanted up there.”

“Not everything.” Tami’s voice was quiet, mourn

ful even. “My mother doesn’t have me. I know that she would want me over any food in the galaxy, any amount of water to drink or warm blankets to cover her... Mum would want me over the biggest, most softest blanket that the northerners could make. She told me so herself.”

“I know she would. And, in time, you’ll see her again.”

Tami nodded thoughtfully.

Faith

Faith New Fleece on Life

New Fleece on Life Ren of Atikala

Ren of Atikala Sacrifice (Kobolds)

Sacrifice (Kobolds) Dusk

Dusk The Pariahs

The Pariahs Reckoning

Reckoning Lacuna

Lacuna Hammerfall

Hammerfall Evelyn's Locket

Evelyn's Locket The Requiem of Steel

The Requiem of Steel Lacuna: Demons of the Void

Lacuna: Demons of the Void Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust

Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard

The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion

Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1)

Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1) The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere

The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere Imperfect

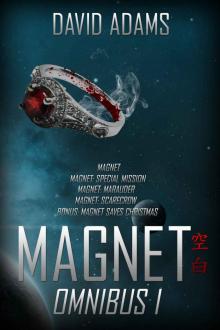

Imperfect Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)

Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)