- Home

- David Adams

Sacrifice (Kobolds)

Sacrifice (Kobolds) Read online

Contents

Copyright Information

Title Page

Blurb

First published in The Dragon Chronicles (2015),...

Dragon's Lair

Sacrifice

Author's Note

Sacrifice by David Adams

Copyright David Adams

2015

Sacrifice

A short story set in the universe of Ren of Atikala

When an egg is laid, it’s a father’s instinct to protect their child.

When a child dies, it’s a father’s instinct to protect their memory.

— Proverbs from the Wisdom of the Wyrmmaker.

Before the Godsdeath we had power. Dragons commanded the arcane and the divine equally. We could have raised our stillborn eggs to life. Such things were not unusual for our kind, especially not those who had magic and motivation. I had both.

Ophiliana was the better fighter. I was the better spellcaster. We were, however, both dragons; magic and muscle in one package, wings that could block out the sun, flame that could burn a horse to the bone, eyes as sharp as eagle’s.

And yet, for all our strength and power, Ophiliana and I could not conceive.

We kept trying, of course. Dead egg after dead egg. We waited.

The humans were not so patient. They pleaded with the gods to return. They threatened. They screamed to the heavens.

And then, all other avenues exhausted, they sacrificed.

First published in The Dragon Chronicles (2015), compiled by Samuel Peralta.

Sacrifice

Fifty years before the destruction of Atikala and the events of Ren of Atikala

“I’m here,” I reassured my mate, Ophiliana the Goldheart, my voice the gentle thunder in the distance; it echoed around the vast, underground limestone cavern that was our shared home. The sound bounced off water and stone, reverberating and distorting, as though a thousand voices spoke with me, punctuating their whispers with drips of water from the ceiling. “The egg has nearly emerged. Be ready to push again.”

The pain of the laying was etched on her face. Rarely did males see such things; this was female’s work, the labour squarely planted on her back. All I could do was give food, water, a reassuring touch.

Despite tradition and both our instincts urging me away, I stayed. We had tried so many times, and this time could be the time; I had to be here for her.

Pain should be shared.

“I am right here,” I said again. Her foreclaw squeezed mine with a grip that was iron. I squeezed back. “With you, beside you, always. We shall endure this together.”

The cave was dark, darker than it had to be. Dim magical lights floated all around but they were barely as bright as candles; rainbow hues reflected off the water, bouncing all around the cave in a coalescence of light that was as subtle as it was deceptive.

Light would reveal the truth. Neither of us truly wanted to see.

Ophiliana’s face contorted and she whined like stressed metal. Her hindquarters twitched and undulated, ripples running across her scales. She gave a tortured groan, shimmering eyes half lidded, her claws tearing lines out of the stone beneath her. There must be a thousand such gouges by now, carved out over the centuries, new ones created every birthing.

And then it ended. Just as it always had. She rested, breathing through her nose, the product of her labours cupped by her tail. A thin shelled egg, the size of a dog, slick with golden blood. It lay on a pile of coins we had set aside for it. All dragons needed a hoard, even hatchlings.

Her eyes, full of worry and pain—the pain that hurt the heart, not the flesh—sought mine. I struggled to avoid them, staring at the egg, imagining its insides. A golden dragon, scales purest metal, a daughter or a son for us both; joy from pain, life from a score of failures, the first success in centuries of trying. It had to be.

“Contremulus,” she said, the words a gentle croak. “Please. Check it for me.”

Hope and hopelessness. This egg seemed like the others; an opalescent sheen over semi-translucent metal, a dragon’s egg to be sure. But was it viable? Time would reveal all.

“Can’t we wait?” I said, finally looking at her. “Do we have to find out right away?”

“I could not bear it,” she said, in a tone that cracked my heart. “I must know.”

The flickers of magical light soared throughout the cave, my mental command stoking them and bringing illumination. The rainbow pattern became a flood, a barrage of light into our home that exalted the creation of this new life. I threw everything into it, forcing the glow to be as fiery white as Drathari’s sun itself, penetrating the shell of the egg from all sides.

I cupped it in both of my foreclaws, Ophiliana doing the same. We watched the tiny thing within—and it was such a tiny creature, barely a foot long, suspended in a floating golden fluid—and we waited for signs of movement within.

And we waited.

“I am sorry,” I said, the words strained with the effort of their telling. “It is my fault.”

“It is nobody’s fault,” said Ophiliana, leaning against me. I draped my wing across her body, drawing her close. “Not yours, not mine. None save the Gods, choosing to abandon us in our moments of need.”

Before the Godsdeath we had the power. Dragons commanded the arcane and the divine equally. We could have raised the eggs to life. Such things were not unusual for our kind, especially not those who had magic and motivation. I had both.

Ophiliana was the better fighter. I was the better spellcaster. We were, however, both dragons; magic and muscle in one package, wings that could block out the sun, flame that could burn a horse to the bone, eyes as sharp as eagle’s.

Eyes that cried tears the size of a man’s head.

To me, this was the greatest evidence of all that the Gods were not missing, not absent, but truly dead. Always had our deities been kind to mortals—and dragons, although nearly timeless and mightier than whole armies, were mortal too—but now tragedies piled up on us, too many to count. Crops wilted and died. Men died of treatable wounds. The magic of the druids could no longer regrow the forests so logging shrank them by the day. Resources became scarce. Blood was shed on every continent; in war, in grief, and in offering.

“My Lord?” Dorydd the dwarf, one of my servants, knelt by the entrance to the chamber. She was barely a child but served us very well. How long had she been there? “How can I help you?”

She knew. Of course she knew. A wave of rage flashed through me—how dare this dwarf intrude on this most private of time?—but logic told me Dorydd may have been there for a long time; I had been so focused the outside world passed by unnoticed. A human would have revealed themselves during the hours of labour, but dwarves were calm and slow as stone; yet patience that paled in comparison to a dragon’s, who could wait for a world to grow and die.

“Thank you,” I managed, “but nothing can be done. Prepare the fluid; we will preserve this one as we have the others. When the Gods return, we shall return our child to life, as we have the others.”

Ophiliana did not approve. I could sense it in her breathing, her heartbeat, the faintest shift of her body; no human could have ever sensed this, but I saw it as clearly as a lit torch at midnight.

“As you wish, My Lord,” said Dorydd. She dipped her forehead to the stone and left. I watched her go, hearing her retreating footsteps echo as they moved up and toward the upper chambers.

“I should hunt,” I said, a lie if ever I had told one. “You will need to regain your strength.”

Ophiliana nestled in against me, curling her neck against mine. “Can you not?” she asked, her voice quiet. “Lady Dorydd can bring us some of those dwarven sweet cakes. I do not need meat.

I need you.”

How I wanted to help her, and how I knew she spoke the truth. What I needed, though, was to be alone for a time.

I said nothing and simply waited.

Dorydd returned, towing a cart covered in cushions and pillows. She gathered the coins, careful not to miss a single one. Then she wiped the egg down with a handcloth, cleaning away my mate’s golden blood. As Dorydd loaded the egg into the cart she looked as I felt; pained to the core, saddened, drained.

“The alchemical solution is prepared,” she said. “I have seen to it.” Dorydd folded the cloth and laid it over the dead egg and then, hesitating as though fearful she was speaking out of turn, addressed Ophiliana. “Do not lose hope, My Lady. These things happen. My mother struggled to conceive for years before my older brothers arrived; just as she had considered all to be lost after a decade of trying…twins. Then two more sons. Then I, and I was not the last of her children.”

I appreciated her attempt to comfort us but her words grated on me. The struggles of dwarves bored me.

“Thank you,” said Ophiliana, dipping her head respectfully. “I am grateful to you for sharing this story with me, Lady Dorydd. I hope, when your own time arrives, you are more fortunate than your mother and I.”

Dorydd’s features twisted, fighting to suppress some deeply hidden emotion. “Thank you,” was all she said, and then she gripped the handles of the cart and began pulling it out of our sleeping chamber.

“I will walk with you,” I said. “I want to see the embalming.”

Ophiliana touched my side, eyes glinting in the dark. “Must you?”

A simple question difficult to answer. “Our loss is not final,” I said. “The Gods will return, and each of these children will live again. They are simply…sleeping.”

Once again she nestled in against me; I resisted, pulling my head away. “Death is not to be feared,” said Ophiliana. “We live and we die; as will our children, a thousand years hence or tomorrow. It is the fate of all to eventually die.” Her voice wavered. “Where is the Contremulus who understood this simple truth? The outside world is a sea of suffering and pain, why must you invite such darkness into your heart as well?”

Lose, grieve, and then turn your eyes to the future. Nostalgia is a craving that can never be satisfied. Wisdom of the Wyrmmaker, patron deity of dragonkind.

My servants did not approve. My mate did not approve. The teachings of the divine, and the wisdom of dragons passed down through the eons all told me that embalming the failed eggs was an unhealthy practice, and the murmurs of my conscience knew it too.

That voice was mostly a whisper now.

“We could…try reanimation.”

If I had suggested she eat her own dung her expression could not be more revolted. “No,” she said, her tone mortified. “Contremulus, no. No.”

“But we could see them. Talk to them. They would have life, of a sort.”

She was silent for a moment. “You are not the only dragon to suggest such things. When my father...” She struggled to say the words, her face tightening. “Died, my mother thought as you did. Eventually a priest dissuaded her. A human. He explained it thusly; the undead are not truly alive. They have the faces of the living and are made from the same flesh, but that is superficial.” Her eyes defocused, half closing. “They are whole in the same way a corpse blended up and sculpted into the shape of a man is a man. All the pieces are there but something is fundamentally wrong. That is no way for your children to live.”

Every word was true. “I know.” Admitting it hurt me.

“Promise me you will never attempt this.” Her voice was steel, hard as anything I’d ever heard. “Promise me.”

“I would promise you the sun and the stars, had I the power.”

“Yet you do not. You can give me this.” She extended a claw, gripping my foreleg. “I want you to say it.”

The words were stones in my lungs, struggling to prevent their escape. “I promise you,” I said, the words slipping between my clenched lips. “I promise you this and more.”

That seemed to satisfy her. The tension flowed out of her. “Do not go,” she said. “Stay here with me.”

I wanted to obey but could not. “I will not be long,” I promised.

“As you wish,” Ophiliana said, kissing my neck. “Know that I love you.”

“And I you,” I said.

Although I left the chamber with Dorydd I did not go far before an irresistible urge overtook me. Without offering explanation of any sort I turned away from the embalming pools and, instead, made my way towards the twisting, winding cavern that lead toward the surface.

I needed to fly.

*****

Higher.

The world dropped away below me as my wings beat, carrying me up into the air, up past the trees and the mountains. Up past the lowest clouds that clung to the tips of the highest mountains, up into the ink black night sky. Up into frigid clouds to be buffeted by their winds; to be bruised and tossed, to struggle against nature itself.

Higher. The world was full of such disappointments. Such deep and personal failures. I needed to get away from it all; away from the shame, the anger, the pain.

I had never climbed so high. My wings ached, my breath came in huge white clouds of mist. The howling chill of the thin air wormed its way between my scales, touching flesh, stealing the heat from my body.

Mountains were flat against the ground. Trees were splotches of green, the towns and cities of the Crown of the World tiny dots of light against the grey snow of the north. Human villages and towns and cities, their feeble lights trying to keep the dark at bay. Night fog rolled in, swallowing Drathari in a blanket of grey.

Dark thoughts swirled in my head. Humans. They had spread across the surface of our world, a rot that slowly corrupted everything they touched. They cut the trees, they mined the hills, they fished the lakes. They took and took and never gave, except when they thought they could gain.

The Wyrmmaker told us all to be kind to those who served us. But he was gone. What did it matter what some dead god told me?

Eventually I could climb no more. My wings beat against nothing; the air was empty, thin, frigid and dry. I had reached the very edge of Drathari, where nobody would see me or hear me.

I roared up into the nothing. Screamed. Painted the night sky with flame. I used my every breath, every ounce of air to vent my rage at the moon, hoping to burn it to cinders. It was my way of dealing with what had happened. The male way.

Females could cry, let their pain ease out like an overstuffed cushion. Their way was to share the load; loss was a wound to be treated with kindness, understanding, compassion.

Males expressed their grief differently but no less powerfully. We took in our pain, made it our fuel, burned it as energy for our journeys. In public we remained strong in the face of pain, suffering, and loss. Males were pillars of strength, giving of their power, but behind the facade of courage our hearts ached as much as any.

In public we wore our masks of stoicism. In private we raged into the dark.

My breath was exhausted, fury played out against the backdrop of the stars and sky. I could fly no longer and folded my aching wings, tumbling towards the ground, a trail of smoke in my wake. It seemed as though nothing below me moved; only tiny patches of cloud drifted apart, imperceptibly slow, as my speed grew and grew.

I plummeted through a blanket of cloud, tail fluttering behind me. Ice broke away from my body, falling as tiny scintillating spears, drifting away from me and finding their own path to the ground.

Perhaps I would follow them to oblivion. Dash my body on the frozen ground of the icy north below and be done with it. The idea nestled into my heart as quickly as it had appeared, and surrounded by a wall of grey nothing it took on a life of its own.

Ophiliana blamed herself for the stillborn eggs. Perhaps it was I that was at fault. Both parents contributed, after all. A stunted seed could not grow in even the most fertile

soil.

Sometimes, when she looked at me, I sensed something in her eyes. A longing for another opportunity. I was not the only gold dragon in Drathari; many others, old and strong, would value her as their mate. After a few centuries of grief, she would move on.

She would find another.

She would find happiness.

It would be better if I was gone.

At least I would know what would happen to me. My body would be found, eventually, then carved up and sold to dragonbone collectors. My teeth would become enchanted weapons. My scales, armour for nobles. This was the fate of all our kind who were not preserved.

I burst from below the fog, expecting the shadowy darkness of a frozen land covered in night, but the surface twinkled with torchlight. A fiery river winding its way out of Northaven. Two thousand men or more, marching north, to the very edge of The Crown of the World.

To our lair.

The humans were coming for us.

My death would have to wait. I flared the tips of my wings, the strain pulling on exhausted muscles and tendons. I used my forelegs as brakes, extending them out, the limbs shaking as the frigid air buffed them.

I pulled up, only a few hundred feet from the ground, and I flew toward our home as fast as I could.

*****

I flew into the wind, my wings aching, and I felt the fire grow in my belly once more; the warmth spread throughout my whole body, melting away the lingering ice.

I cast as I flew, flashes of magic lighting up the night. Arcane power flowed through me, reinforcing my scales, sharpening my claws. Preparations. I was good at them.

As I drew close, it was apparent that the approach of the human armies had not gone unnoticed. All of our servants stood by the cave entrance to our lair, armed and armoured. Even Dorydd had a halfling’s sword.

Ophiliana was in human form; long blonde hair tumbled down her shoulders and her back, and she wore a fine suit of plate mail, her hands folded neatly in front of her.

Faith

Faith New Fleece on Life

New Fleece on Life Ren of Atikala

Ren of Atikala Sacrifice (Kobolds)

Sacrifice (Kobolds) Dusk

Dusk The Pariahs

The Pariahs Reckoning

Reckoning Lacuna

Lacuna Hammerfall

Hammerfall Evelyn's Locket

Evelyn's Locket The Requiem of Steel

The Requiem of Steel Lacuna: Demons of the Void

Lacuna: Demons of the Void Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust

Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard

The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion

Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1)

Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1) The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere

The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere Imperfect

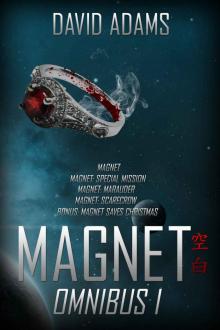

Imperfect Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)

Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)