- Home

- David Adams

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity Read online

Contents

Copyright Information

Blurb

Books

Dedication

Title Page

Velsharn

Prologue

Act I

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Act II

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Act III

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Epilogue

The Lacunaverse

Lacuna: The Ashes of Humanity by David Adams

Copyright David Adams

2013

Humans thought that they could stand amongst the older races. They believed, in their hubris, that the perils of interstellar travel could be mastered within a single generation. That they would be spared the wrath of the Toralii.

Now humanity lies in ashes. The cradle of our civilization, Earth, is nothing more than a charred husk, a dead world in an empty solar system in an unremarkable corner of the galaxy.

The war is over.

We lost.

Captain Melissa Liao and the remaining band of Humans, numbering barely in the tens of thousands, hold the future of their entire species in their hands. They must settle a new world, encounter friends and enemies new and old, and plant the seeds of hope in the ashes of humanity.

Book four of the Lacuna series.

Books by David Adams

The Lacuna series (science fiction)

Lacuna

The Sands of Karathi

The Spectre of Oblivion

The Ashes of Humanity

The Prelude to Eternity

The Requiem of Steel (coming 2015)

The Kobolds series (fantasy)

Ren of Atikala

The Scars of Northaven

The Empire of Dust (coming 2015)

Stories in the Kobolds universe

The Pariahs

The Pariahs: Freelands (coming 2015)

Sacrifice

Stories in the Lacuna universe

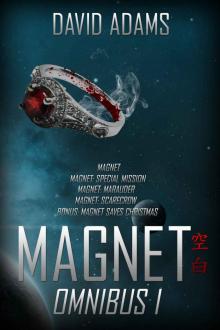

Magnet

Magnet: Special Mission

Magnet: Marauder

Magnet: Scarecrow

Magnet Saves Christmas

Magnet: Ironheart (coming 2015)

Faith

Imperfect

Other Books

Insufficient

Insurrection

Injustice (coming 2015)

Who Will Save Supergirl?

Evelyn’s Locket

––––

A writer does not write in isolation,

for we are the sum of their experiences.

It is from these experiences that inspiration comes.

I thank my family, who allowed me to be who I am,

My friends, who love me in spite of me,

And as always, to my readers.

You made all this possible.

Special thanks to UFOP: Starbase 118 for teaching me how to write,

and Shane Michael Murray,

my tireless proofreader, motivator and partner in crime.

––––

Lacuna

空

白

The Prelude to Eternity

“When time is spent, eternity begins.”

- Helen Hunt Jackson

PROLOGUE

The Beach of Bones

*****

Copiapó

Chile

Earth

Seven months after the devastation of Earth

LIEUTENANT RACHEL “SHABA” KOLLEK OF the Israeli Space and Air Arm first thought the misty sand beach in front of her, on the southern shore of Chile, was beautiful. However, as the boots of her space suit hit the ground, she discovered it wasn’t made of sand at all.

It was bones.

Millions of fish bones blanketed the area, some barely larger than a pinhead, some the size of a basketball. The Toralii worldshatter devices had seared the land and boiled the oceans. Earth’s aquatic life had died en masse, and the bones of countless sea creatures washed up all over the planet’s shores as a new beach. The threshold between scorched land and dark, oily, barren sea was a thin line of death.

The Falcon transport Piggyback, Shaba’s brand new baby and the second ship to bear that name, idled behind her, landing ramp extended. She chewed on the end of her cigarette, adjusted her sealed bubble helmet, and stepped into the mist. Her suit chirped at her. The atmosphere was a thick mix of carbon dioxide, ash particles, and water vapour. She exhaled, blowing cigarette smoke against the clear Plexiglas hemisphere separating her from the death soup, the smoke inside the thin polymer dimming the clouds outside.

The atmosphere of Earth was an opaque wall of death. If anyone had survived the initial bombardment—and analysis of the attacks had determined that most Humans had—they would now be dead, burned in walls of flame, choked on an atmosphere they could not breathe, or starved because the water and food that remained would be ruined.

Modern human beings were so dependent on the structures of society—agriculture, medicine, transport—that they could not survive such a calamity. That beach was a suitable landing spot because it had been largely spared the orbital fire. The cities, the urban centres, would be much worse off.

Her parents had died on that planet. Most of her friends had died on that planet. They would be missed.

The man who had raped her, nearly fifteen years ago, had died on that planet. He, not so much.

A lifetime ago she had been sixteen, and he a trusted son of a friend of the family. He was handsome, too—charismatic, tall and athletic, with women just falling over themselves to be with him. He had the pick of anyone he wanted.

It turned out he liked the ones who struggled a bit. The joy was in the conquest, the having of what had been denied him.

Somehow, in defiance of all logic, they had dated for three years after the first time. There were other times. He drank. She still stayed. Shaba didn’t claim to understand what had happened, just that it had.

Now that guy was just a body on a corpse planet—one of billions. His bones were bleaching in the sun, just like the fish. She shifted her weight and crunched some under her boots.

That knowledge didn’t feel good. It didn’t feel bad. It was mostly a nothingness, an emptiness, neither vindication nor defeat—somewhere in the middle.

She hadn’t killed him. Yet he was dead. Her fantasy made no sense.

Even in death, he was taking things from her.

“You shouldn’t be smoking in that thing.” Mace, one of her gunners, grumbled through the comm unit in her ear.

“Yeah?” She chewed on the end of the cigarette. One of their crew, still back on the Rubens, was nicknamed Smoke. He smoked in his suit all the time—enough to earn himself that nickname. Who was Mace to judge her? “Well, maybe you shouldn’t be so fucking bald.”

“A shaved head’s a man’s haircut. Nothing good comes from those coffin nails, you know. That’s what I tell Smoke. Don’t be like him.” Static squealed over the line. Mace said something she missed.

“Say again,” she said.

The radiation caused interference; the worldshatter device had ignited practically every fossil fuel reserve on the planet and, in the process, vented a bunch of radioactive material into the atmosphere.

“I said, I used to give him shit about it too. What happened?”

Shaba adjusted a dial on her wrist, and the noise faded. “Nothing,” she said. “Don’t worry about it. Look, this place is a ruin. Not bad to visit, but we ain’t ever m

oving back here.”

“I know, I know.” Mace’s voice was totally normal, as though he were observing a football game he had no interest in. “Well, there’s nothing here. Let’s go check out NORAD.”

NORAD, better known as the Alternative Command Center nestled in the Cheyenne Mountain nuclear bunker in Colorado, had been designed to laugh in the face of even an overwhelming nuclear response. NORAD was one of the few places Humans might still be living.

Living Humans still on Earth—strange that it had come down to that. Shaba considered all the events that had ever happened on the planet—so much history, so many things to mourn. Out of all the men in history—caesars, kings, emperors, inventors, painters, artists, creators, rulers, and destroyers—all she could think about was that one guy and what he’d done—how he was gone.

And how she felt nothing at all.

“Whatever,” Shaba said, using her tongue to push the cigarette butt against her visor, snuffing it out as she closed the hatch. Shaba didn’t bother to strip out of her suit and walked back to the pilot’s seat, passing Mace on the way.

“Hey,” he said, his sullen face undercutting his optimistic tone. “How’s it looking closer to the ground?”

“Not much better from out the window.” She walked past him, to the cockpit. Their conversation continued by radio.

“Yeah,” said Mace. “I had hoped it was just a little bit less than total shit.”

“Well, it ain’t.” Shaba slid into the pilot’s seat and commenced the engine start-up sequence. The ship came to life with a pained groan. It was a new ship, and she felt its pain. The increased ionisation and acidic atmosphere could not be good for Piggyback’s hull, and there were entirely rational and reasonable justifications for why the reactionless drive’s pitch harmonics might sound off, but to Shaba, the ship seemed to be protesting simply being there. That place. That dead world.

No bird could live there.

Shaba pulled off her gloves. “NORAD’s near enough to seventy-six hundred kilometres away, boys, so we’ll be heading out of atmo’ for this one.” She worked as she spoke, tapping her fingers over the preflight checks. The start-up sequence was second nature to her and came as naturally as breathing. “Little hop-skip-jump into space, and we’ll be hobnobbing with the last survivors of Earth.”

“Assuming there are any,” said Bobbitt, their tail gunner. “Ain’t nothing I can see here but ashes.”

Artificial gravity and inertial dampening systems, check. Life support, check. Transporters, check. Optimal flight path… she was still working on that one. The navigational computer chirped. Check and cross check. Her distance estimate was right on the money. Manoeuvring engines, check. “Yeah,” she said, the work complete. “What a shithole.”

The ship drifted lazily into the sky as the reactionless drive defied gravity. It rose like a lost balloon, steadily accelerating, a thin cone of pressure forming ahead of them as they broke the sound barrier. Grey sky gave way to empty space. The ship was silent as it skimmed across the skin of Earth’s outer atmosphere and then plunged back in, wreathed in flames. When the flames died and Piggyback re-entered the atmosphere, the mountains of Colorado presented themselves, blackened, charred, and scoured of all life. Gone were the trees. The city of Colorado Springs stood dead, broken, and empty, scorched black from the impact of the Toralii worldshatter devices. As the ship descended, bodies of cars grew from tiny dots, their paint stripped away by the blasts. They stood piled up against the sides of highways, useless rusted wrecks. The ship rocked as it dropped, buffeted by the constantly howling wind that tore around the planet, mourning the dead.

The location of the Cheyenne Mountain facility was no secret. The various agencies there had been heavily involved in the production of the United States contribution to the Pillars of the Earth, the TFR Washington. Finding it was easy.

Getting in was another story. Piggyback touched down near the North Portal, a cracked and broken concrete tunnel leading into the mountain. Shaba nestled the ship as close as she could get without scratching the paintwork. Satisfied she could do no more, she powered off Piggyback’s systems and met with the rest of the crew in the cargo area.

Thick blast doors protected that most secure facility against direct nuclear strikes, and even the Toralii worldshatter devices hadn’t been able to penetrate the huge mountain housing the critical structure. They had food, water, supplies enough to last. If anyone had survived inside, they could still be alive.

Mace held up one of the heavy-duty lasers they had brought for the job, attached to a long set of industrial electricity cables. A thick fiberglass and reinforced Kevlar collapsible airlock took up most of the cargo bay, a giant snake ready to unfurl on a ring of wheels near its mouth. “Don’t you think it’s better to just knock?”

“Pretty sure they won’t hear us.” Shaba pulled her gloves back on and checked her suit. The others did similarly. “Those blast doors are too thick.”

“Assuming anyone’s alive in there.” Bobbitt struggled with his helmet, until it clicked on with a faint hiss. “They’re not answering their radios.”

His negativity was frustrating. Shaba double-checked her gloves pointlessly. Why had she even taken them off? “All the antennas would have been on the surface, destroyed in the blast. With no active satellite connections remaining, they probably turned everything off after the first few weeks.”

“Or they could all be dead.” Mace rolled his shoulders. “Just saying.”

“Yeah, well, don’t just say,” said Shaba. “We’re here to make sure that they’re alive and, if they’re not, recover anything we can. Survivors are important—technology too. It’s all very well fabricating simple computers and the like, but if we want new ships, we need plans. Schematics. Anything we can use to build stuff.”

“Surprisingly,” said Mace, “I actually did read the mission briefing.”

She glared at him. “That’d be a first.”

A moment of uncomfortable silence pervaded.

“Hey,” said Bobbitt, “you okay, Shaba?”

“No.” There was no sense denying it, not to the crew with whom she had flown and fought for what seemed like a lifetime. “I am pretty far from okay right now.”

“Yeah,” said Mace. “It creeps me out just being here.”

How could they understand? How could she explain it to them? She didn’t try and just forced herself—as she had been doing for most of the trip, most of her life—to put the whole thing out of her mind and focus on the task at hand.

“Yeah,” she said and, confident that her team had their suits on correctly, pressed the button to lower the launch ramp. The howling wind once again whipped through the open door, blowing dust and grime into the otherwise clean cargo bay.

That was less than ideal. The true effect of the worldshatter devices wasn’t completely known. The weapon didn’t leave radioactive debris, but the background radiation of an Earth made uninhabitable was substantial. Cleaning the bay was a job for another day.

With Mace leading the way, the four of them walked down the long tunnel toward the facility, Shaba and Bobbitt wheeling the collapsible snake behind them. The further in they went, the darker it became.

“No lights,” said Bobbitt. “Not a good sign.”

They all switched on their suit-mounted lights.

Shaba focused on pulling the heavy airlock. “They probably just turned them off to save power.”

Bobbitt mumbled something into his microphone too quiet to understand. Nobody bothered to answer. They carried on. Soon, the heavy, reinforced blast doors of the facility loomed out of the dusty dimness, scratched and faded but intact.

“It’s closed,” said Bobbitt. “That’s a good sign.”

“Beats the alternative,” said Shaba.

They worked together, aligning the umbilical to the blast doors, sealing it with a faint hiss. The ship’s atmosphere flowed into the tunnel.

Mace unfolded the laser’s tripod a

nd set it down. “You know,” he said, “there was this one missile silo I visited as a kid, right? It had blast doors like these, but on the front was the logo of Domino’s Pizza. Right below that, they had the words: Delivery in thirty minutes or less, or your next one is free!” He sighed into the microphone. “Was kinda hoping these guys would have a sense of humour too.”

The others laughed. Shaba didn’t. “Well,” she said, “let’s get to knocking.”

Bobbitt shrugged off his backpack and pulled out a hemispherical device the size of a football. With a pained grunt, he lifted it and magnetically attached it to the blast doors. It was an ultra low frequency emitter, one of the pieces of technology the Washington had for transmitting sound through objects, a device that was specifically engineered for large solid masses.

“Should be on,” he said. “There’s a second set of doors behind this one, but they might still be able to hear us.”

Shaba touched a button on her suit’s wrist. The half sphere lit up, shivering as if in anticipation. “Attention, Cheyenne Mountain facility. This is Lieutenant Kollek of the Israeli Air and Space Arm.” She could feel the vibrations in the floor below her feet, could hear it as though her own voice was coming from the floor. “We’ve arrived with a ship to transport you away.”

Nothing immediately—that was expected. She gave them a moment to let the message sink in, assuming it had been received at all. “The blast door is linked to our ship; it’s safe to open, as long as you do so slowly.”

More stretches of nothing. The Piggyback crew waited patiently.

“Maybe no one’s home,” said Bobbitt.

Shaba had come a long way to stand in front of that metal door. She wasn’t going to give up just yet. “Procedure is to wait twenty-four hours. If there’s no sign from within, we cut our way in and see what we can salvage.”

Faith

Faith New Fleece on Life

New Fleece on Life Ren of Atikala

Ren of Atikala Sacrifice (Kobolds)

Sacrifice (Kobolds) Dusk

Dusk The Pariahs

The Pariahs Reckoning

Reckoning Lacuna

Lacuna Hammerfall

Hammerfall Evelyn's Locket

Evelyn's Locket The Requiem of Steel

The Requiem of Steel Lacuna: Demons of the Void

Lacuna: Demons of the Void Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust

Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard

The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion

Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1)

Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1) The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere

The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere Imperfect

Imperfect Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)

Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)