- Home

- David Adams

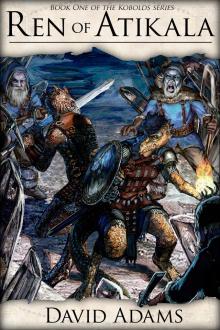

Ren of Atikala Page 4

Ren of Atikala Read online

Page 4

THE DAY ATIKALA WAS DESTROYED was a special day for me.

I woke up with a start, the memory of a dream still raw and vivid, every detail seared into my mind. It was another night filled with haunting dreams. This one was a memory, that of my second birth.

I disliked being unable to control my mind while I slept, but sorcerers always dreamed. Our dreams reflected the faint sliver of powerful blood in our veins, a body stuffed with too much soul, the excess spilling into the night hours. It was the price we paid for our arts.

The dreams, sometimes original and sometimes mirrors of my own memories and experiences, stayed with me and refused to fade when my waking hours came. Each one was infused with power and omens, the beating of golden wings, and the comforting yet intense heat as I exhaled a wreath of flame that could melt stone.

But prophecy was dead. There were no portents in my dreams. Nobody had been able to see the future for hundreds of years, to the point that some wondered if such things ever existed. Yet sometimes I wondered, somewhat fearfully, if the memories appeared in my sleep not because they had happened before, but because they would happen again.

I uncurled myself from the cool stone floor of the quarters that served as my lodgings, the simple home of a warrior. I was careful not to let my claws scratch any of the nine others sharing the floor with me, all huddled together around a pile of coals for warmth.

Of those who lived with me, I always awoke first, and always because of the Dreaming. I climbed to my feet, stepping over and around my fellows as I gingerly made my way over to the wooden chest, six inches by nine and six deep, the vessel for all my worldly possessions.

It was rare for kobolds to own anything at all, but the sorcerers amongst us tended to have keepsakes. Memories of our younger years, things to ward away nightmares or to grant nights without dreams. My box held only a red velvet bag. I lifted it, tugging open the string and upending the contents into my hand.

Eggshells. Golden fragments of my egg, still glowing with a faint light after all these winters. They were so small in my palm. I turned them over and over, listening to them rattle against each other. I had once lived completely within this thing. It had been my entire universe, all I knew and experienced, but I had eventually broken free of it and seen so much more.

It was like this city. Few kobolds outside the Darkguard had left Atikala, but I knew there was a much wider world out there. A world of fantastic creatures, of monsters and evil. Was Atikala my new egg? My new existence waiting to be shattered?

I had so many questions but had found no answers. Why had the egg not burned? Why did it continue to glow to this day? Why was I golden coloured when all around me were rusty or black?

“What am I?” I spoke to the broken pieces, hoping the fragments of my birth device would have words to speak back at me.

“Talking to yourself again, Ren?”

Ren. It meant nothing. With my name struck from the register after my death, Ren was what everyone called me.

I didn’t have to turn around to know who was speaking. The low, deep voice belonged to Khavi. Khavi was an oddity; he was the only male in our patrol team. Only one in twenty kobolds were male.

I had reached six winters, and Khavi had been the first assigned to breed with me when the season was right. He had successfully bred with another of our patrolmates already and came from a respectable line of strong warriors. There was nothing to dislike about the pairing, but I wasn’t sure about the idea of mating with him. Not that it mattered. I knew I had to do my duty. The numbers of the city had to grow.

“No.” I tipped the eggshells back into the pouch, careful to catch them all, then slipped the string around my neck.

“I’ve heard you talking to that thing before,” Khavi said. I heard him stand, claws squeaking faintly on the stone. “You should throw it away. It’s not healthy to keep talking to it.”

“It’s mine,” I said, turning around to face him, “and I’ll keep it if I wish. Sorcerers are permitted personal effects.”

“That doesn’t seem fair.”

“Life’s not fair,” I said.

“But it’s unnatural to own things.” It was clear by the way Khavi spoke he was reciting one of his lessons. “The community’s goods belong to everyone. To own is to restrict, and to restrict is to devalue. Why would you devalue the society’s property, that which is owned by all?”

I didn’t have a valid answer to the wisdom of the city leaders. Instead I dodged the question and stretched out my limbs, joints cracking as I exercised them. “We should get to the armoury. We have our patrol today.”

Khavi’s muzzle split in a grin, revealing a wide field of razor sharp teeth. Males had duller teeth than females, but Khavi seemed to be an exception. Despite his narrow chest and shorter stature, Khavi was as strong as any female. “We do. Our first patrol as seniors. Our first time in charge.”

I walked to the thin curtain that divided our room from the hallway, pulling it aside and stepping through. Kobolds had no doors, no locks, no internal dividers. Doors were to keep intruders away. Fellow kobolds were not intruders; the cloth was simply to reduce noise.

“Are you sure you’re up to this?”

Khavi’s red eyes glowed with an eager light as he moved to follow, the two of us stepping into the tight passage with a throng of others, all moving either to our duties or returning from them. “I have been waiting for this day for some time,” he said, moving with me through the bustling crowd. “You have your dreams, and I have mine. They’re somewhat less literal, I admit, but it’s the same thing.”

I stepped over a glowbug that scurried underfoot, its bright light flaring as my footclaw scraped its back. “It’s not, it’s different,” I tried to explain for the hundredth time. “My dreams are not ambitions, merely…things. Things that I see and feel. Not what I want to be or do.”

“Fortunate that you do not wish to be a dragon!” He laughed, a rasping noise that drew the attention of other kobolds in the corridor. “I fear you are much too small for that, goldling.”

Goldling. My derisive nickname since hatching. I clamped my jaw together, careful not to sever the tip of my tongue with my teeth. “Thank you,” I hissed. “I hadn’t noticed.”

Soon the tunnel widened away from the sleeping quarters and out to the city proper. Atikala was built into a subterranean cavern, and despite its massive size, had few buildings. Sleeping quarters were built into the walls, making the best use of the limited open space our people could find. Khavi and I crossed the plaza, a flat area teeming with kobolds moving between sections, until we arrived at the central part of the city.

The great Dome of Daily Reflection. We knelt obediently, as all were expected to do in the morning, reflecting on the lessons we had learnt throughout our lives, focusing on the one we anticipated would be the most important for the day.

As this was my first day as patrol leader, I drew upon a lesson Yeznen had given me about the enemies of our people. His words flowed through my mind as clear as the day I’d first heard them.

We are cousins to dragons. If fate were righteous and fair, this entire world would be ours, with the dragons at its head and us by their sides.

But fate is neither righteous nor fair. We may have the blood of our masters in our veins, but never let your arrogance blind you to reality. We live in a world surrounded by hate, by hungry steel in blood-soaked hands.

Humans. Elves. Gnomes. Jealous of our gifts, these wicked races of darkness are your enemies. They hate you as you hate them, seeking only your destruction and the denial of our destiny. Never hesitate to spill their blood, for they would end you in a heartbeat.

The righteous can have no mercy for monsters. Say it with me now, children! Shout it to the stones above! Let all who hear our voices tremble in fear!

No mercy for monsters!

No mercy for monsters!

No mercy for monsters!

“So I hold, Leader,” I said to the dome.

<

br /> “So I hold, Leader,” said Khavi. I stood, then offered Khavi my hand. As I pulled my friend to his feet, I wondered which lesson had played through his mind. It was probably the same as mine. “No Mercy for Monsters” was his favourite.

Our observance completed, we headed to the open-air bazaar that served as the city’s armoury.

Kobolds did not own things, so we had little use for walls inside the city. No locks or guards protected the weapons and armour supplies; they lay on open benches unattended, and the two of us attracted no attention as we approached our allocated table.

“Do you think we’ll kill anything?” asked Khavi, hoisting his well-worn suit of armour, its humanskin leather plates squeaking as he pulled it over his head. I did the same with mine.

“I doubt it,” I answered, adjusting my straps, making sure the armour was snug and tight without snagging on my scales. “It will be as every patrol we had as wyrmlings. Uneventful.”

“That’s dangerous thinking,” said Khavi, drawing a belt around his thin midsection, and then strapping the shin guards to his legs. “Our eyes should always be alert. If you expect no danger, you’ll find none until it finds you. Yeznen told us that.”

Yeznen was too paranoid for my taste. “The gnomes, may the shit of the dead Gods fall on them, don’t value the minerals below them, and the humans above us know better than to burrow where they are not welcome.”

Khavi reached out and tapped a claw to my leather breastplate. “These one’s didn’t.”

“Perhaps it is good we might encounter some raiders then,” I said, reaching up and tucking my pouch of eggshells under the plates. “The community could always use more armour.”

We shared a laugh, and then retrieved our weapons. Khavi easily hoisted the large two-handed sword that was his trademark weapon. He eyed me as I lifted the delicate short-blade I favoured, slipping my buckler onto my arm. It was an action I’d done hundreds, if not thousands, of times.

“You are a sorcerer, are you not?” asked Khavi, a variation of the same question he asked every time we donned our equipment.

“Yes,” I answered, an edge of exasperation creeping into my voice. “I am.”

“You cast spells, then.”

“You know that I do. You ask me almost every time we’re here.”

Khavi smiled. “Perhaps I’m expecting a different answer one day. I just want to know why you remain with the patrol teams instead of becoming a leader. You choose to be a warrior.”

“Yes, I choose to be a warrior,” I echoed. This was enough of a reason, enough justification.

“Then I fear I will never understand you,” said Khavi, strapping the weapon over his back. “Nor will I understand your desire to choose things. I go where the Leaders tell me to go.” His voice took on a serious edge. “You know that the only reason they permit you to train as a warrior is those scales of yours.”

My annoyance bubbled and grew into insult. I turned to him, hissing faintly. “You know I hate it when we talk about this.”

“About being a warrior or about being a Goldling?”

“About my scales. About what I am. It’s just a colour.”

Khavi affixed a firm stare on me. “And what is that? Perhaps your hue is more than an innocent pigment. Perhaps you draw your power from the blood of the rotten golds.”

Gold was the colour of the hated metallic dragons, cousins to the silver, bronze, brass, and copper.

The metallic dragons were our mortal enemies. The gold wyrms were lofty and uncaring, the silvers were collaborators with our various enemies, the bronze were foolhardy and destructive and the brass were deceptive and manipulative. The last of them, copper dragons, were maliciously cruel and wicked, delighting in torments and riddles. Plain out-and-out evil. In Atikala the coppers were hated above all the other metallic dragons, especially as one lived relatively close to a neighbouring gnomish settlement.

Nothing had come of the copper’s presence yet, but our leaders were always wary. There were no known gold dragons nearby, something that had certainly helped secure my survival. Nobody could be sure of anything except that I manifested spells, but my colour had always been a source of confusion and shame.

Khavi was being more inquisitive than usual, and I didn’t like it. I snarled and thumped my fist into his shoulder. “Don’t,” I warned. “It’s just a pigment. It means nothing.”

He held up his hands defensively, taking a step back. “As you wish,” he said. “It’s just a pigment.” He gave me another smile. “Look, forget it, okay? How about we just enjoy this special day of ours?”

I wasn’t so ready to forget Khavi’s words, but I pushed them to the back of my mind. “Fine.”

I wheeled around and stormed away from the armoury to meet our newly assigned patrol, heading directly for the gates that protected Atikala. Khavi and I climbed the great stairways built into the sheer walls of the city, towards the top of the cavern, watching Atikala shrink as we climbed. When we reached the top, we were hundreds of feet above the buildings below, the entire city stretched out before us and bathed in a golden glow.

I wanted to admire the view, as I had many times before, but Khavi's impatient grunt reminded me we had a job to do. We crested the last few steps to the tunnel out to the underworld, sealed by a vast iron door. The guards gave us passage without question. Their eyes were fixed on the outside. Something coming from the inside was no threat to our community.

We had not gone more than a hundred steps, however, when a soft, quiet voice caught our attention.

“Ah, your first patrol. I’m glad I could be here to see it.”

It was Tzala’s voice, my mentor and a sorceress like me. Tzala was truly ancient, but age did not affect kobolds as it affected the other races; we simply grew more powerful and did not wither away. Workers and warriors would inevitably die in their line of work, but a good sorcerer could live a very long time indeed, and Tzala was the best sorceress I knew.

She too owned things. Her possession was a necklace, silver with a red stone at its heart, and she was never seen without it.

I gave a deferent bow of my head and Khavi followed suit.

“Good morning, Leader,” I said, “I hope not to disappoint with my performance.”

Tzala’s maw split in a wide smile. “Somehow I do not think you will. Long have I awaited this day, and I hope, so have you. I remember my first patrol well and with fondness.”

“I shall endeavour to be attentive and walk with purpose.” I paused, inhaling slightly. “Actually, I had hoped to see you afterwards, Leader. I was going to talk more to you about Tyermumtican.”

Tzala’s expression clouded slightly, and out of the corner of my eye, I could see Khavi pulling a face.

“I have explained to you before,” said Tzala, “the copper dragon is far too powerful and distant for you to visit on your own, and we do not have cause to mount an expedition solely to ask him of your lineage.” Her tone softened. “I know your pain, Ren. I know you want to know where you came from, and why your colour is so unusual, but the matter is settled.”

I bowed my head once again. I knew once a Leader said that a matter was settled that should be the end of it, but words found their way out. “I understand, Leader, but it is…not fair. All in Atikala know their lineage, but my records were destroyed when my egg was thrown in the furnace.” I tried to keep my tone even. “Regrettably, they did not possess my endurance.”

“I know,” said Tzala, “and I wish I could help, but I cannot.”

“The right to launch an expedition is in your hands—”

A prod in the side from Khavi’s elbow silenced me.

“I am sorry,” said Tzala, folding her arms in front of her.

“Of course.” I was silent for a moment, then raised my head curiously. From the corner of my eye, I could see Khavi readying to elbow me again, but I spoke up anyway. “Forgive me Leader, but why are you here? Rarely do sorcerers step beyond the gates of the city.

”

“Strange words, coming from you.” Tzala chuckled and cast a fond gaze upon me. “Am I not permitted to see my Firstclaw, my most promising student, away on this most special day?”

Firstclaw of her students? It would be quite an honour to be Firstclaw at my age, but I wrinkled my nose. “You flatter me, Leader, but I am not worthy.”

Tzala waved her hand dismissively. “An accolade fairly earned. You should wear the title with pride.”

“I…perhaps, but I am not fond of titles, Leader.”

“So I have learnt.” Tzala shook her head in amusement. “This attitude will change in time, as you move beyond your role as a warrior and grow your power as a sorcerer. Soon you shall acquire a taste for them.”

Unable to disagree about the future and deferent to her wisdom, I bowed my head again. Tzala reached out and patted my snout.

“Good luck, my student. I’ll see you when you return, for we have much to discuss.”

“Discuss?” My heart leapt. Perhaps my words had won her over.

Tzala’s face held a mysterious smile. “Regarding the next step in your training.”

“Of course,” I said, trying to disguise my disappointment, but I couldn’t help a faint rustle running through my scales. “Thank you, Leader. I shall speak to you on our return.”

With that the elder kobold turned and retreated back into the city. She nodded courteously to the guards as the iron doors creaked open and the light of Atikala poured in. A million glowbugs bathed the greatest kobold city in the entire north in light, shining through the open gates. Tightly packed dwellings filled the bowl of a limestone cavern to the brim.

The iron gates closed behind Tzala, and I opened my mouth to speak, to have idle conversation with Khavi while we waited for the rest of our patrolmates.

A planet-shaking roar stole the words from my tongue. The stone beneath me buckled like a wave on water. Drathari roiled and heaved, the stone itself breaking free of the ceiling and falling around us. I was thrown almost into the ceiling. As I plummeted back down, veins opened in the ground, cracking like a spider’s web as the unyielding rock rose and fell. The glowbugs fearfully winked out their lights, plunging the underworld into darkness.

The noise abated, and all the world fell into silence as suddenly as it began. My right arm burned; I’d fallen on it, wrenching the tendon. I lay sprawled on the ground, cloaked in the pitch black, surrounded by silence. The pain eased, and I was convinced I was dead, crushed under the tide of stone, and I could think of nothing.

The sound of coughing made me realise I had been holding my breath.

“Ren? REN!”

“Khavi!” I inhaled a lungful of stone dust and began coughing too. “Khavi?”

Slowly the glowbug’s fear died, and the light returned. I found Khavi, cowering with his hands over his head. I linked my arms with his as we coughed and choked down air, fighting to breathe.

The rumble of moving earth tore my gaze to the great iron gates of Atikala. They were buried under a mountain of stone, and I knew somehow that this was the end of my home, and that things would no longer be as they were.

I scraped my broken claws and bleeding fingers on the pile of unyielding rocks, pulling aside chunks of soil and debris. My breath came in ragged gasps, choking on the thick limestone dust that filled the air and caked my scales in a layer of white. I dug in a frenzy until I hit a flat slab of iron. One of the gates to the city, bent and twisted out of shape, blocked my tunnelling. I hooked my fingers underneath and tried to move it.

My injured arm screamed at me to stop. I ignored it. Despite my efforts the ruined gate wouldn’t budge. It weighed tonnes, and the stone above it was heavier still.

I moved over, trying to squirm underneath it. The faint smell of blood, not mine or Khavi’s, met my nostrils. I shifted a tiny rock, and a hand, fingers twitching, reached for me. A survivor.

No. This was a fleshy, pink hand, not the scaled limb of a kobold.

Fear silenced the pain in my arm; there were none but kobolds inside Atikala. Where had this creature come from? I needed to find out. Had we been attacked by gnomes? Had saboteurs bought down the gates? The leaders would interrogate it, but only if I could save it.

“I’m coming!” I said, then braced my legs against the stone and pulled.

I fell on my rump. The arm was severed at the elbow. The fingers continued to twitch, as though the hand were reaching for me, trying to grab me and drag me down with it to the lands of the dead.

The owner couldn't answer any of our questions. I threw the limb away.

How deep had the stone collapsed? “It’s no good here!” I shouted to Khavi on the other side of the tunnel. “I’ll start on the left side!” I had to find someone, anyone. A living soul. But if we couldn't, I needed to get through to Atikala. To save my home.

The gate and the arm meant we were close. I moved to another part of the blocked tunnel. We had no shovels, nothing except our claws. My short sword was far too weak and thin and Khavi’s two-handed blade too unwieldy.

“I’m through!” Khavi said between laboured gasps. “I can see the main cavern!”

One opening was all we needed. I looked to the blood-soaked arm I found, now still. There was a body further in there. A monster. But beyond that were kobolds just like me, crushed by the stones. I could do nothing for any of them. They were dead, and if they weren’t, they soon would be. Trying to save anyone at the wall was hopeless. If anyone was alive, they’d be on the other side. Further down, in the deep caverns. That’s where the wyrmlings were. The hatcheries full of eggs. They needed saving most of all.

Abandoning my fruitless attempts to dig through a hundred times my weight in stone, I dragged myself to my feet and staggered towards Khavi, staring hopefully at the hole he made. It was under a foot wide—hardly enough for even the most diminutive of kobolds to fit through. Several of his rust coloured scales had broken off, and he was bleeding, little trickles of black blood painting dark circles on the ground.

“Can we widen it?” I asked, inspecting the sides. It was a crack between two boulders.

“I was hoping your magic might be able to help,” said Khavi.

I clicked my jaw, grinding my fangs together. This conversation was old and stale, one we’d had too many times. “Dragon magic creates fire,” I said. “I’m not a dwarf. I can’t talk to stone.”

There was more to it than that, but a complex discussion on magical theory was not a priority at this stage, and even if it was, Khavi would never understand.

“Well, you’re thinner than me,” said Khavi. “Maybe you can squeeze through, then get help.”

The thought had already occurred to me. Khavi helped me tug off the weapons and armour, and they clanked against the rubble with a dull thud, a sound that should have been a lingering hollow echo. The world was smaller now. It closed in on the two of us, resisting our efforts to help anyone who had survived.

I crouched down to the edges of the crude hole Khavi had dug, then squeezed up against the entrance. I almost fit. I sucked in my middle, tightening the muscles holding my bones together, wriggling and writhing. Getting through meant helping the rest of the city. Getting through was my duty. The crying of my arm was joined by other parts of my body as they scraped, squeezed, and dragged through a hole that was just too small.

My scales snagged on a jagged edge. I was stuck. Then Khavi kicked me in the backside. Twice. The force tore several scales off my injured shoulder, and a third kick sent me through. Gold blood trickled from my wounds.

“Thank you,” I said, groaning as I pulled myself up to my feet and looked towards my home.

Atikala was crushed under a mountain of stone. Its high domed ceiling, once smooth and polished to a mirror shine, now lay on the floor, jagged and cracked like a mouth full of broken teeth. The bowl that was the limestone cavern of Atikala was filled with stone and debris, reaching almost up to the collapsed gate to the city. Tens of thousands of lives had b

een snuffed out in an instant. Generations destroyed. Our culture, our history, entombed beneath the stones.

My eyes darted from rock to rock looking for movement, looking for hope, but there was none. Had I not known the truth, had I not seen it with my own eyes, none could tell that a city once stood here. The glowbugs that once carpeted the roof had fallen with the ceiling. Everywhere the glowing fluid from thousands of crushed bugs made jagged yellow lines, seeping out through the cracks in the fallen roof. Underneath all that stone was every single kobold I’d ever known; my entire life was consumed by the falling earth.

“What are you waiting for?” said Khavi, trying to see through. “Get the diggers to come and widen this hole. Then we can start searching for survivors in the other tunnels.”

“There are no diggers,” I said, my voice just a whisper. “There’s no anyone.”

“What?” said Khavi, hissing through his nose. “Bah. Hold on, I’m coming through.”

It took Khavi longer to get through, but when he finally scrambled out, he joined me in stunned silence, staring out at the ruins of the city that had withstood goblin attacks, gnome invasions, and countless waves of human raiders. Atikala had stood every test of time, survived every trial. Except this.

The silence of it was the worst part. The city only moments before had a sound, a distinct voice like no other. It was more than the chatter of voices, the clang of mining equipment, and the scrape of claws on stone. It was far too many kobolds crammed into a hollowed out stone cavern. This was the living and beating heart of my people. A collective organism, breathing, moving, talking. There should have been noise, a dull murmur like the constant company of a snoring spouse.

The only noise was our quiet breathing as we stared at the piles of rubble that used to be our everything.

“What do we do now?” asked Khavi.

The roof of the cavern stretched up, higher than I could see, a faint point of light at the top. I could not comprehend how high it was, but it was too far. I looked over my shoulder to the hole we’d come through, back down the corridor away from the city and climbing on a gradual slope. The tunnel led to the gnome settlement above and the humans on the surface above that. The tunnels led to our enemies. To doom.

“We leave I suppose. Go to Ssarsdale. Get help.”

Khavi stared out at the faintly glowing debris, his tail limp on the stone, eyes wide but pupils as small as buttons. “Ssarsdale? It’s a moon’s journey away by the tunnels, and they're surely collapsed. We’ll have to go over the surface. How will we find our way?”

I followed his gaze, watching the air slowly settle through shafts of light from beneath the rubble, but to my eyes they looked more like ghosts rising from the ground.

“Well, the only way to go is up.”

Faith

Faith New Fleece on Life

New Fleece on Life Ren of Atikala

Ren of Atikala Sacrifice (Kobolds)

Sacrifice (Kobolds) Dusk

Dusk The Pariahs

The Pariahs Reckoning

Reckoning Lacuna

Lacuna Hammerfall

Hammerfall Evelyn's Locket

Evelyn's Locket The Requiem of Steel

The Requiem of Steel Lacuna: Demons of the Void

Lacuna: Demons of the Void Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust

Ren of Atikala: The Empire of Dust The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard

The Soul Sphere: Book 02 - The Final Shard Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity

Lacuna: The Prelude to Eternity Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion

Lacuna: The Spectre of Oblivion Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1)

Legacy Fleet: Hammerfall (Kindle Worlds) (Khorsky Book 1) The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere

The Soul Sphere: Book 01 - The Shattered Sphere Imperfect

Imperfect Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)

Magnet Omnibus I (Lacuna)